The winners and highly commended organisations of the 2022 Indigenous Governance Awards show that community works best when First Nations people are in the driver’s seat.

June 2022 maked the first time the Indigenous Governance Awards had been able to take place since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Judged on innovation, effectiveness, self-determination, sustainability, and cultural legitimacy, the winners epitomised Indigenous-led excellence.

In particular, finalists were commended by the judges for demonstrating profound resilience in the face of lockdowns and restrictions, adapting to protect their communities, as well as continue their work in the toughest of circumstances.

The following organisations – Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council Human Research Ethics Committee; the Koling wada-ngal Committee; South Australian West Coast ACCHO Network; Brewarrina Local Aboriginal Land Council; and Wungening Aboriginal Corporation – were all either winners or highly commended in their categories, and their stories encapsulate self-determination and community control in action.

Best in the West: Koling wada-ngal Aboriginal Corporation

l-r: Koling wada-ngal Aboriginal Corporation Co-Chair, Karen Jackson, and Board Member Deb Evans. Photo: Abe Byrne-Jameson

The Koling wada-ngal Aboriginal Committee (Highly Commended, Category 1 – Outstanding examples of Governance in Indigenous led non-incorporated initiatives) was established in 2013 in response to a lack of cultural support services in the City of Wyndham in the south-west Melbourne.

Wyndham is one of the fastest growing regions in Australia and home to the highest proportion of Aboriginal people in Greater Melbourne.

The committee – now the Koling wada-ngal Aboriginal Corporation – identified that community needed space to gather, connect, share, create, grow, learn and be safe.

Wyndham City began planning and building the Wunggurrwil Dhurrung Centre in 2014 with consistent input from community and the committee. The centre officially opened in 2019.

Read the rest of Koling wada-ngal’s story in the October edition of Reconciliation News.

Health outcomes through ethical research: AH&MRC HREC

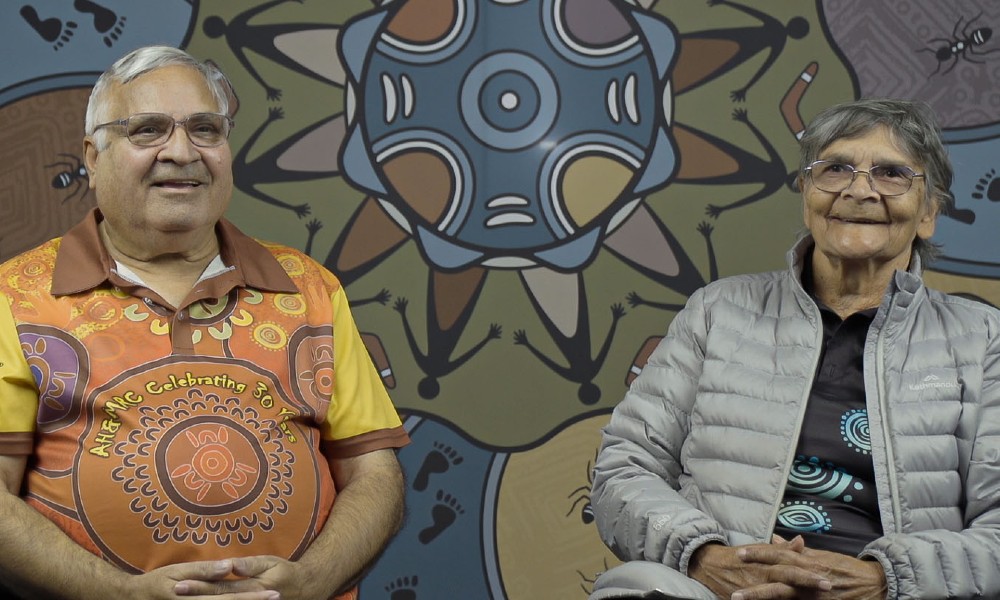

H&MRC HREC Community Representatives, l-r: Uncle Danny Kelly and Aunty Rochelle Patten, sitting in front of the ethics committee’s 25th anniversary artwork by Aunty Rochelle. Photo: Abe Byrne-Jameson

The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Human Research Ethics Committee, or AH&MRC HREC, (Winner, Category 1 – Outstanding examples of Governance in Indigenous led non-incorporated initiatives) was established in 1996 to ensure all Aboriginal health research in NSW was conducted in an ethical and culturally safe way, with the aim of improving health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the state.

CEO of AH&MRC Robert Skeen explains, ‘Historically, research has not always been a positive experience for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. Too many times it has had a negative, traumatic, and racialised impact upon these communities.’

Distressed Aboriginal participants of research were presenting to Aboriginal Medical Services across NSW with concerns over what they viewed as invasive, inappropriate and unnecessary health research in their communities.

There was a need to address these issues, and this need formed the foundations of the Committee’s dual governance structure, combining western methods with traditional community governance.

Going forward: Brewarrina Local Aboriginal Land Council

Some members of Brewarrina Women’s Business group, l-r: Tracy Gordon, Charlotte Boney, Narelle Renalds, Belinda Boney, Courtney Boney, Denise Renalds, Urayne Warraweena and Natalie Boney. Photo: John Reidy

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have consistently fought for ‘land back’: the return of lands and waterways stolen during the invasion of this continent. This has been an unbreakable demand reiterated across generations.

In response to these demands in 1984 the NSW Government passed land rights legislation. The Aboriginal Land Rights Act NSW saw the establishment of a statutory body, the NSW Aboriginal Land Council and a network of 120 local Aboriginal land councils (LALCs) across the state. One of these was in the western NSW town of Brewarrina.

A year after the NSW legislation was passed the Brewarrina Local Aboriginal Land Council’s (BLALC) inaugural Chairperson, Ernie Gordon Snr, lodged a claim for about 8,000 acres in 1984. That claim, Land Claim 1043, is now the longest unresolved claim in the state.

This lack of progress has not daunted the BLALC (Winner, Category 2 – Outstanding examples of governance in Indigenous-led small to medium incorporated organisations), and it has continued to make significant progress in providing a voice for its community and acquiring land for cultural, economic and social benefits.

Read the rest of Brewarrina’s story in the October edition of Reconciliation News.

Heads up high: The Wungening Way

Wungening’s Boorloo Bidee Mia program is designed and led by Aboriginal people and informed by the rough sleeping community. Photo: Richard Wainwright/AAP Image

As the COVID-19 pandemic swept across Australia at the start of 2020, and lockdowns became the order of the day, governments scrambled to find accommodation for thousands of people experiencing homelessness. Those living on the streets were suddenly found beds in empty motels.

Some letter writers to newspapers even hopefully suggested that COVID-19 may lead to the end of homelessness in this country. But it wasn’t to be, and after the lockdowns ended, so too did these unprecedented efforts to house Australia’s people who are experiencing homelessness. Nine thousand of Australia’s estimated 116,000 people who are homeless are in Western Australia with about 1,000 of these sleeping rough on the streets. Forty per cent of these identify as First Nations people.

Wungening was born in 1988 in response to the need for an Aboriginal-designed, culturally appropriate alcohol and substance abuse service in Perth. Just over a year ago it added homelessness to this list.

Read the rest of Wungening’s story in the October edition of Reconciliation News. g

Strength in collective voice: SAWCAN

The SAWCAN team during a planning session. Photo: Robert Lang

Imagine a wheelchair-bound man in your community. Imagine this man dragging himself on his belly across the dirt to visit his family, or to watch a local game of footy, or attend a family funeral.

He is forced to do this because there are no footpaths in his remote community and his wheelchair cannot traverse the uneven, dusty terrain. This was a real scenario confronting an Aboriginal organisation in rural and remote South Australia.

South Australian Aboriginal communities shared these frustrations of lack of access and fought to establish their own ACCHOs. Today there are five Aboriginal controlled health services on the state’s west coast, providing professional primary healthcare to First Nations people in the region. In 2018, the South Australian West Coast ACCHO Network (SAWCAN) was born (Highly Commended, Category 1 – Outstanding examples of Governance in Indigenous led non-incorporated initiatives).

Read the rest of SAWCAN’s story in the October edition of Reconciliation News.